Earth rotates, the Sun rotates, the Milky Way rotates – and a new model suggests the entire Universe could be rotating. If confirmed, it could ease a significant tension in cosmology.

The Universe is expanding, but exactly how fast is a contentious question. Two different methods of measurement return two very different speeds – and as the measurements become more precise, each becomes more certain. This discrepancy is known as the Hubble tension, and it’s reaching crisis levels in physics.

So for a new study, physicists in Hungary and the US added a small rotation to a model of the Universe – and this mathematical massage seemed to quickly ease the tension.

“Much to our surprise, we found that our model with rotation resolves the paradox without contradicting current astronomical measurements,” says István Szapudi, an astronomer at the University of Hawaii.

“Even better, it is compatible with other models that assume rotation. Therefore, perhaps, everything really does turn.”

According to their calculations, the Universe could take trillions of years to complete a single spin – and given that it’s less than 14 billion years old, it still has a long way to go to finish even its first rotation.

That may sound like the cosmos is taking its sweet time, but the team found that it’s close to the maximum possible speed. Thankfully this doesn’t require any information to move faster than the speed of light, so time doesn’t bend back on itself and cause a bunch of time travel paradoxes.

The idea of a rotating Universe is not without precedent: a recent study suggested the possibility to explain an odd observation that galaxies tend to favor spinning in one direction over the other. In a static cosmos, the split should be more or less 50-50.

But this is the first time the idea has been applied to the Hubble tension.

It might sound like semantics, but solving this tension is crucial for our understanding of the cosmos. It’s based around a value known as the Hubble constant, which represents the rate of the expansion of the Universe.

Astronomers use the Hubble constant to calculate the age and size of the Universe, the distances to objects beyond our galaxy, and the influence of dark energy. If we start whacking recklessly at this foundational block, the whole Jenga tower that is the Standard Model of Cosmology could come crashing down.

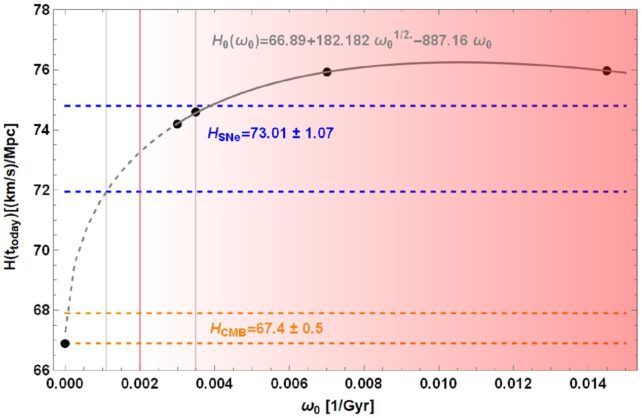

One way to measure the constant involves signals from the early Universe – specifically, the cosmic microwave background (CMB), and baryon acoustic oscillation. These reliably return a Hubble constant of around 67 kilometers per second per megaparsec.

Closer to home, astronomers rely on ‘standard candles’ – objects in the local Universe, like certain types of stars and supernovae, with a known intrinsic brightness. Comparing that to their apparent brightness from afar allows their distance to be calculated, which can also be used to figure out the Hubble constant. Only in this case, it seems to be around 73 kilometers per second per megaparsec.

It might be tempting to round both numbers to 70 and call it a day, but each method’s error margins have since been trimmed right down to 1 or 2 either side. Both numbers are close, but confidently different.

But a spinning Universe, according to the new study, plugs the gap by saying that both are kind of true. The effect of the rotation becomes more pronounced the farther away astronomers look, which explains the discrepancy between the two methods.

If the entire Universe is spinning, it could raise some fascinating questions about reality. What force could possibly set this in motion? One particularly mind-boggling hypothesis suggests our Universe is located in the center of a black hole inside another Universe. After all, black holes also rotate at close to the maximum possible speed.

It’s fun to think about, but before we embark down that rabbit hole, the team says the next step is to produce a full computer model incorporating a rotating Universe. This could help identify predictions that astronomers can search for in real-world observations, to confirm or rule out the idea.

The research was published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.